Getty / Ford Foundation / Bargaining for the Common Good

Getty / Ford Foundation / Bargaining for the Common GoodTwo years ago, as COVID-19 spread to every corner of the world, the virus ushered in a slew of urgent needs while exposing entrenched issues of inequality and injustice. It was nonprofits that sprung into action to respond to the moment. They stepped up to tackle the pandemic’s sweeping impacts, providing immediate relief, protecting the rights of workers, addressing the concerns of historically excluded communities, and reimagining the systems and structures that are critical for a fair and equitable recovery.

While the demand for their services surged, organizations grappled with their own futures. With the markets in panic and economic activity in decline, they were forced to rethink fundraising, pull back on their programs, and shift their operations. Nonprofits are no stranger to financial hardship and shifting donor interests—in fact, half of organizations struggle to become financially sustainable. But COVID-19 posed an existential threat, requiring funders to reevaluate their support, become more flexible in their grantmaking, and innovate to increase the resources they could offer.

That’s what led us to issue a social bond to strengthen the social justice sector, the first ever issued by a philanthropy on the United States taxable corporate bond market. Most major foundations traditionally spend a little more than 5% of their assets in a given year, the minimum required under federal law for tax-exempt organizations, to allow their endowments to grow and continue to give. This unprecedented time called for an unprecedented measure. By issuing the bond—a financial mechanism more often practiced by governments, universities and companies—we were able to make the markets work for justice and nearly double our grantmaking to more than $1 billion to respond to the needs of our grantees—and society at large.

Over the last two years, we listened to and learned from the organizations we fund, and provided them with the additional support they needed to not only meet the demands brought on by COVID but to thrive, grow, and evolve in their work. They adapted and innovated amidst crisis and chaos, pivoted to take on challenge after challenge, and ultimately became more nimble, resilient, and impactful organizations. Below are three examples of the impact we’re seeing from our social bond.

Advancing justice in the workplace—and beyond

As COVID-19 spread around the world, so did the uncertainty and vulnerability for workers and the communities they live in. Unions and community groups had long pushed for workplace safety, access to health care, and other essential worker protections. Now their fight took on an altogether different order of urgency and necessity.

Bargaining for the Common Good (BCG) helped workers meet the moment. The collective of unions and community groups expands the structure of traditional union contract negotiations, which usually bargain for expanded benefits and rights within the workplace: wage increases, medical coverage, health and safety practices, etc. Instead, BCG’s expansive model of collective bargaining holds corporations and employers accountable to enact positive changes that will improve employees’ lives in and beyond their workplaces, thereby improving communities as a whole. The negotiations become wider campaigns focused on tackling the larger problems of racial justice, wealth inequality, affordable housing, environmental sustainability, and more. As BCG argues, the problems of injustice ripple outward from the workplace—so, too, should the solutions.

As the pandemic deepened inequality across the country, unions and community groups in the BCG network responded swiftly, pushing their teams to the edge of their capacities. The network mobilized groups in Minnesota, California, and Illinois to support calls for eviction moratoriums, rent cancellations, and other pushbacks against corporate landlords that were raising rents and neglecting safety measures. In Connecticut, BCG united 48 labor, community, and religious organizations to demand a fair budget that would reduce the state’s racial and economic disparities and prioritize the needs of families and workers over tax breaks for the wealthy. The collective also demanded better wages and protections for nursing home workers, who faced major staffing shortages and were provided such woefully insufficient personal protective equipment that they had to resort to wearing trash bags during shifts.

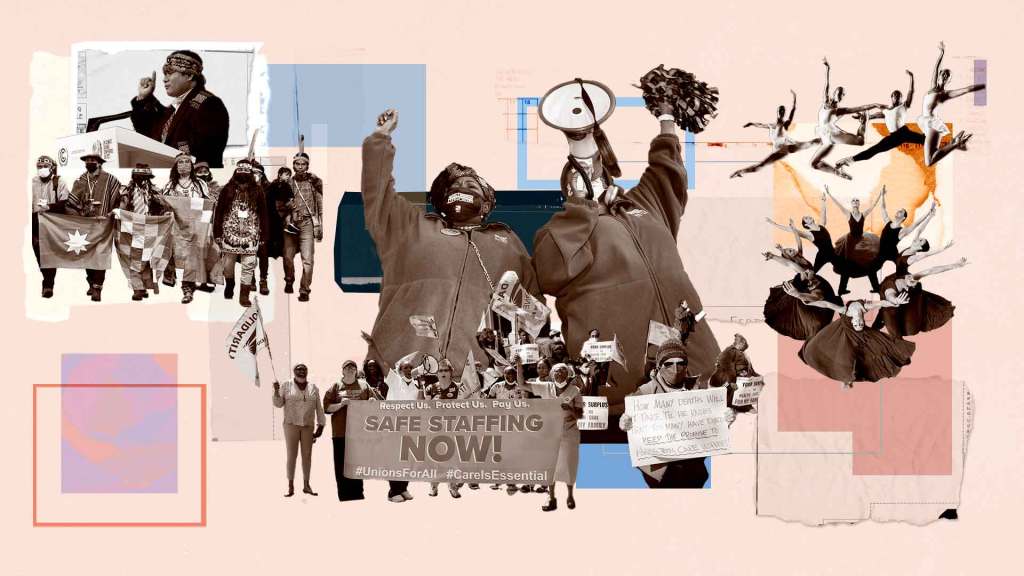

Bargaining for the Common Good

Bargaining for the Common GoodUnion organizers and workers march to demand revised budgets with increased funding for employee and community services.

In January 2021, amid these efforts, BCG received a $4 million grant from the social bond. “It dramatically increased our capacity, both at the national and local levels,” said Marilyn Sneiderman, a member of the BCG executive committee and the executive director of Rutgers University’s Center for Innovation in Worker Organization. BCG was able to sustain its many labor initiatives and hire much-needed staff to coordinate campaigns and lead trainings for unions and community groups across the U.S. With the additional funding, the collective also fostered new partnerships between organizations in Minnesota, Illinois, California, Tennessee, and across the Northeast and even entered new areas, including Missouri, where it quickly established a leadership role in the numerous campaigns for affordable housing spreading across the state.

Its impact was perhaps most pronounced in Connecticut—where, due in part to the crucial support from the social bond, BCG was able to expand its campaign for a fair state budget, which ended in a significant increase in funding for health care. The new budget allotted resources for mental health services, including $5 million in funding for mobile crisis units, and a $5/hour wage increase for nursing home workers, ensuring frontline health professionals have more than just applause, but the wages and protections they deserve.

Honoring America’s diverse cultural institutions

Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) cultural organizations are no strangers to operating under tight conditions. Despite being traditionally underfunded and operating with lean budgets, they all work to share the beauty of their art with audiences and their communities. While all arts institutions experienced major challenges at the onset of the pandemic, BIPOC organizations were dealt an even tougher blow, their revenues erased and programming canceled overnight. With no end in sight for lockdown, and their stages darkened and doors closed indefinitely, many faced permanent closure.

Ballet Hispánico is one such group. At the start of 2020, the famed New York dance company, founded in 1970 by the Puerto Rican and Mexican American dancer and choreographer Tina Ramirez, had already established an ambitious slate of programming to celebrate its 50th anniversary. Then the pandemic struck, upending all its enthusiastic plans. When the company should have been celebrating a remarkable milestone, Ballet Hispánico struggled to stay afloat.

Another is East West Players in Los Angeles—the longest-running Asian American theater company in the U.S. that has staged over 100 plays and musicals about Asian American experiences. The company struggled during months of lockdown, especially because it did not operate with an endowment and had a modest emergency reserve. Its uncertainty felt especially cruel in a time of rising violence against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders across the country—when the nuanced, uplifting stories of East West Players could have even more resonance.

Accessibility Statement

- All videos produced by the Ford Foundation since 2020 include captions and downloadable transcripts. For videos where visuals require additional understanding, we offer audio-described versions.

- We are continuing to make videos produced prior to 2020 accessible.

- Videos from third-party sources (those not produced by the Ford Foundation) may not have captions, accessible transcripts, or audio descriptions.

- To improve accessibility beyond our site, we’ve created a free video accessibility WordPress plug-in.

The social bond offered these groups, and others like them, a lifeline. In September 2020, we launched America’s Cultural Treasures, an initiative to honor the diversity of artistic expression in America and provide critical funding to Black, Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous arts organizations to help them weather the pandemic. We partnered with more than 40 funders to deliver over $276 million in new grants to more than 100 arts organizations across the country—including Ballet Hispánico and East West Players.

The impact was immediate. With the funds received from America’s Cultural Treasures, Ballet Hispánico were able to keep its lights on: It retained staffers and kept their health insurance active, and developed a sophisticated virtual platform to air performances and classes. Its artists were able to continue working daily online and bring in income, and Ballet Hispánico was able to expand its cultural imprint by hosting seminars and creative programming about the organization’s history of intersectionality and support for Black and brown artists. Happier still, the company was able to bring its Latinx cultural outreach to one of their largest stages ever—the 2021 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade—and hold its triumphant 50th anniversary gala in spring 2022.

East West Players also thrived with their additional funds. The company was able to continue operations, share funds with artists, and rebuild its slate of programming for future seasons. East West is currently open for its 56th season and recently honored the actress Michelle Yeoh at its annual Visionary Arts Gala. Now the group—as well as Ballet Hispánico and the rest of the organizations supported by this initiative—is looking ahead towards many more years of meaningful contributions to America’s cultural landscape.

Responding to the moment in Indonesia

In July 2020, Indonesia overtook India as the epicenter of Asia’s COVID-19 outbreak. Hospitals were overwhelmed and low on ventilators, oxygen tanks, and other life-saving equipment; many sick patients were forced to quarantine at home without medication or aid. Nearly 25,000 people died by January 2021. By August, the national vaccine initiative was lagging; only 18% of the eligible population had been fully vaccinated, and new variants were rising in the country. The situation was even more dire for the country’s 40 million Indigenous people and 28 million people with disabilities, who were geographically and physically unable to access the scant resources available.

In November 2021, as part of our social bond, we granted $500,000 to Philanthropy Indonesia to address this inequity in vaccine access. Along with Climate and Land Use Alliance and several other grantees—the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago, the Indonesian Association of Women with Disabilities, and the Association of Philanthropy Indonesia—Philanthropy Indonesia launched an Access to Vaccine coalition to help Indigenous people and people with disabilities obtain vaccines.

Joel Redman/ If Not Us Then Who

Joel Redman/ If Not Us Then WhoApai Janggut, a member of the Indigenous community of Sungai Utik in West Kalimantan, Indonesia.

The campaign received widespread support, leading Indonesia’s president to instruct the government to accelerate the country’s vaccination efforts. Shortly after, the Ministry of Health issued a notice that any Indonesian citizen could be vaccinated in any health facility or center, regardless of showing proof of permanent address or having a national identification number—a significant step forward, as many millions of Indonesians do not possess either forms of ID.

This year, the Indonesian government announced that around 80% of the total population has received a complete two doses of the vaccine—with many of the remaining unvaccinated being Indigenous people and those with disabilities. Progress has been made in leaps, but there is still work to be done—and the Access to Vaccine coalition is ready for it. Currently, the coalition is working with Indonesia’s Ministry of Health, police, civil registry, and other leaders to expedite the vaccination process for everyone in the country. It is gathering data on the number of Indigenous peoples and people with disabilities and their geographical locations to monitor that the Ministry of Health’s commitment is honored by all vaccine providers, providing medical equipment, and creating travel networks and mobile units to make vaccines accessible for those who have difficulty traveling or live in rural areas. The coalition is also creating public education campaigns, including on Tik Tok, and working with journalists to fight disinformation.