UAW’s Historic Strike Win Has ‘Huge Implications’ for Texas Autoworkers

The revitalized union is coming after Toyota, Tesla, and other non-union carmakers.

Labor scholars say the success of the United Auto Workers’ recent strike against the so-called Big Three automakers will have “huge implications” for auto workers nationwide, including those at General Motors’ highly profitable plant in Arlington and at non-union carmakers as well.

The union won tentative contracts last month that include a major pay raise among other benefits. The deal is awaiting final ratification by members, but the effects have already been felt for the approximately 3,800 non-union workers at Toyota’s major San Antonio plant. Toyota on November 1 announced about a 9 percent raise, more time off, and other benefits. UAW president Shawn Fain called it a “UAW bump.” And he said Tesla, with its headquarters and a large plant in the Austin area, will be a target of organizing efforts.

The new UAW contracts are also a major help to workers who since the late aughts have been hired at the Big Three (General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis) plants at significantly lower pay scales under the “two-tier” system, which will be brought to an end.

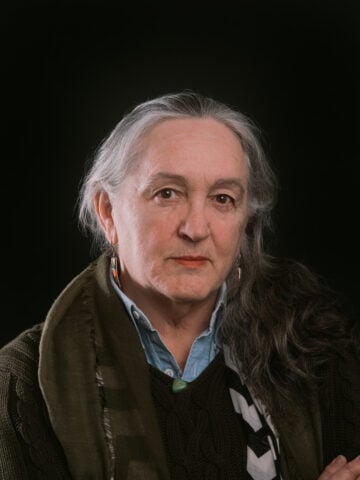

Rutgers labor studies Professor Rebecca Givan said the strike is the beginning of a revival for American workers and their unions—and for collective action and militancy. Workers got “massively better offers” from the car companies after UAW called the strike, she said.

Fain said the “stand-up strike” method deployed by his union was a turning point toward bringing power back to the working class. Many of the victories included in the contracts represent a return to workers of benefits they’d lost over the last several decades, especially around the time of the Great Recession, when the union accepted concessions to keep the car companies from going under during the nation’s financial crisis.

“We started asking for some of our stuff back,” materials handler Ethan Pierce, a 23-year veteran at the GM plant in Arlington, told the Associated Press. “They didn’t want to give it to us.” Inflation has meant that average hourly pay for auto workers dropped by nearly 20 percent since 2008, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Meanwhile, profits at the three major companies almost doubled in the last decade, and CEO pay has gone up by 40 percent.

The UAW’s first-ever strike against all three of the major automakers at once lasted, in all, about six weeks. Rather than walking out of all plants across the country, the union added one plant at a time, with GM last. When GM wouldn’t budge on certain issues, the union widened the strike to include the company’s plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee. Two days later, the strike was over. The union reached a tentative agreement with General Motors on October 30, after agreeing to similar contracts a few days earlier with Ford and Stellantis, the multinational company that makes Jeep, Dodge, and Chrysler, as well as other vehicle lines.

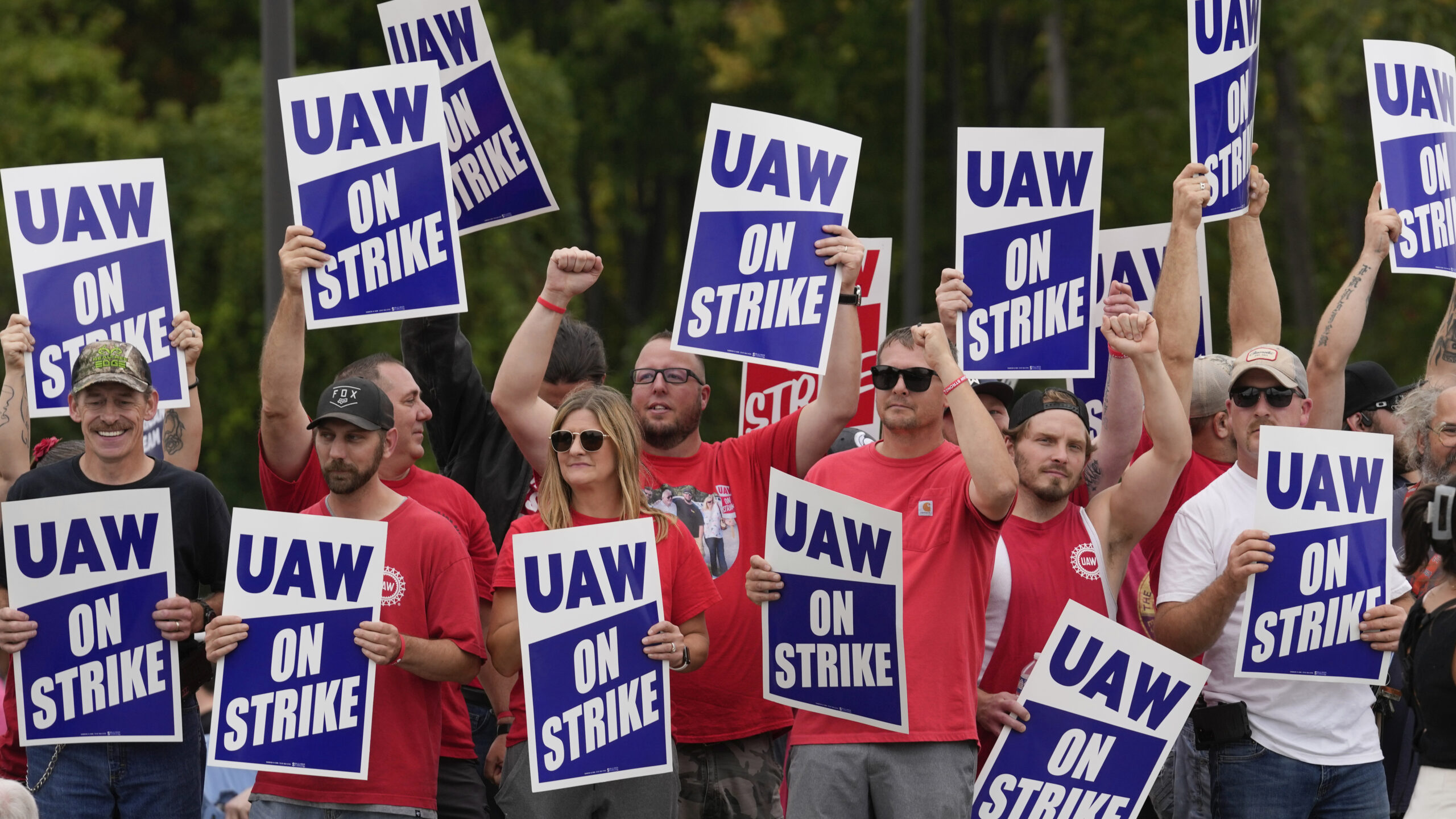

In Arlington, during the late October strike, frequent honks of support from motorists on the nearby State Highway 360 frontage road were music to the ears of strikers. Some drivers stopped to roll down a window, lean over, and offer fist bumps. Regional UAW leaders said they saw the same kind of support all over Texas and the South. They’re hoping to ride that increasing public support, a tight labor market, and the success of the strike to organize other automakers’ plants and related industries around the country.

“We have a tremendous amount of calls coming in” from workers looking for UAW to come to their shop, said UAW Region 8 director Tim Smith, who represents the union in Texas and other Southern states. What is happening with the Big Three, he said, “could change so many people’s lives.” For instance, workers at electric-vehicle battery plants operated by the three companies will now come under the companies’ main contracts with the UAW or otherwise become more open to union organizing. Because electric vehicles represent a fast-growing share of the auto market, organizing there represents a significant move for the union’s future.

During the strike, a Ford Motor Company executive—the great-grandson of Henry Ford—had urged workers to join with the companies to battle foreign automakers. Fain’s response, in a statement, was that “Workers at Tesla, Toyota, Honda, and others are not the enemy—they’re the UAW members of the future.”

Referring to Tesla and to Elon Musk’s attitude toward unions, Fain said the UAW “can beat anybody. … It’s gonna come down to the people that work for him deciding if they want their fair share … or if they want him to fly himself to outer space at their expense.”

In the tentative contracts with GM, Stellantis, and Ford, which must be ratified by UAW members, workers got the promise of a 25 percent wage increase between now and April 2028; reinstatement of the cost-of-living adjustments they gave up in 2009; and an end, by 2028, of the two-tiered wage scheme that has been a sore spot with union members.

The two-tiered system, a scheme that allows companies to pay newer workers at lower pay scales than those already on the job, came back into existence when the union granted concessions during the 2008-09 financial crisis. Newer workers get worse pay and benefits for doing the same job as better-paid colleagues. As Smith described it, “We’re not going to continue to have people working side-by-side with one making $28.50 an hour and the other making $15.”

Givan said the tier system and the loss of cost-of-living increases were “two of the biggest pieces the union gave up to help save the companies” over a decade ago. The system means some workers were receiving “hardly a living wage,” she said.

Another key victory for the unions is that the new contracts, Givan and others said, will give unions some say over plant closures, a change that could be critical for union towns.

“The companies conceded that the union has a say in whether a plant can be shut down or not,” said Nelson Lichtenstein, a labor historian at the University of California, Santa Barbara. If a car company shuts down a plant that it had agreed to keep open, “the union can go on strike” at plants across the country, he said.

What union members apparently didn’t get was a return to anything like a 40-hour week without mandatory overtime. Union members and others told the Texas Observer during the strike that they expected the contracts to put some new restrictions on mandatory overtime. But those restrictions weren’t obvious in the text of the new Ford-UAW contract, nor did UAW officials return calls asking for information on such provisions in the other two contracts.

“We want to work 40 hours a week just like everyone else,” said one GM detail worker in Arlington, who asked that his name not be used. He said six-day work weeks are routine at the GM plant and that the company can demand even seven-day work weeks for up to 90 days.

Tamara Scott, 42, was holding up a sign nearby. She said it’s easy to detect among her colleagues the results of too many hours on an assembly line, for too many days a week, for years. “I see people—young people —every day, wearing back braces, ankle braces. … They’re hurting, but they’re just trying to make it,” she said. Six-day work weeks mean there’s little time for family, “for a life.”

Both Lichtenstein and Givan said companies would rather require extra days from current workers, even with overtime pay, than hire new workers with expensive benefits.

The mandatory overtime provisions have been used by automakers since the early 1980s, Lichtenstein said, at the beginning of what he called “the corporate offensive against unions” in this country. Real wages in the industry have been declining since about 2007, he said, with some small increases in 2019.

Lichtenstein said several factors strengthened the UAW in the recent strike. Important among them was the election of a “new militant group” to the union’s leadership, including Fain, the well-spoken and no-holds-barred president who took office in March.

“We’re coming out of a period where unions were not so bold,” Givan said. These days, she said, “Younger workers are very, very interested in unions. They see the economic difference” that unions can make.